How to Draw Syntax Trees With Too X Bar Syntax

Part Of: Language sequence

Followup To: An Introduction to Generative Syntax

Content Summary: 800 words, 8 min read

Explaining Substitution

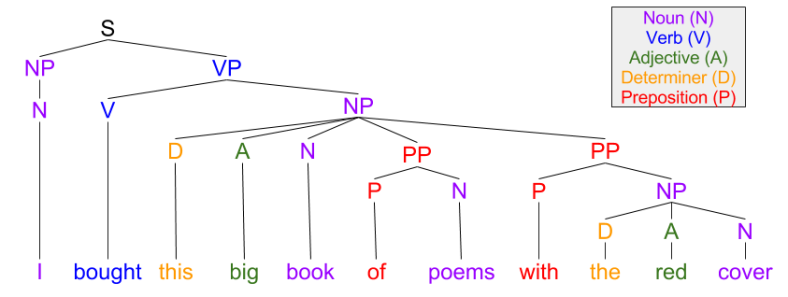

Consider the sentence "I bought this big book of poems with the red cover".

In everyday language, we often replace words and phrases with indexing words like "one". Call this indexing replacement .The meaning of these words can be obtained from the context.

At first glance, indexing replacement seems to target a branch in the syntax tree. For example:

- I bought that big one of poems with the red cover ("one" replaces the noun)

- I bought one ("one" replaces the entire noun phrase)

But there are several other substitutions don't follow from branch replacement:

- I bought that big one.

- I bought that small one

- I bought that big one of poems with the blue cover

Perhaps our notion of noun phrases is too flat. Perhaps we need additional nodes to describe structure within the noun phrase. We will call these intermediate nodes N', (where N → N' → N'' = NP):

This new tree successfully predicts all substitution phenomena, by modeling "one" as replacing various "N-bar" nodes:

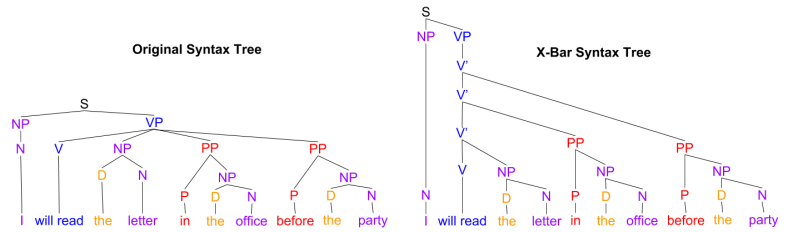

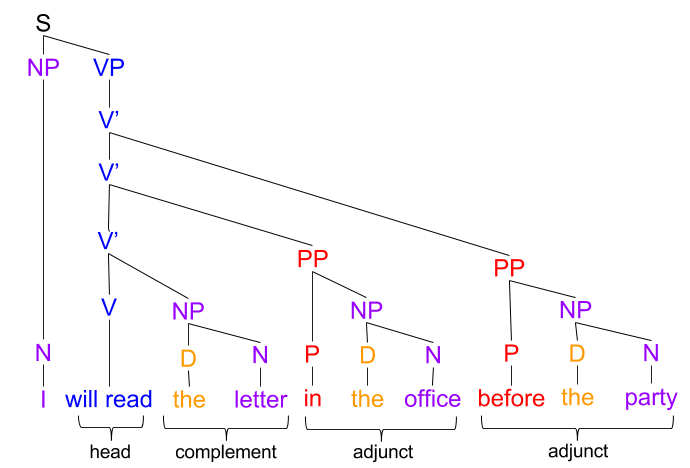

We can similarly introduce depth to our verb phrases (VPs), by using intermediate V' ("V-bar") nodes:

The X-Bar syntax tree provides a simple explanation of the "do so" substitution effects:

- I will do so in the office before the party.

- I will do so before the party.

- I will do so.

A General Theory of Phrases

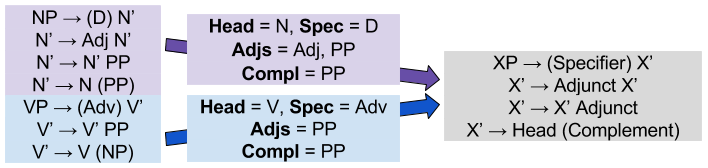

We can revise our original NP and VP rules to reflect our intermediate N' and V' nodes:

What if noun and verb phrases are instantiations of a more general phrase structure? Just as group theory identifies overlap in the axioms of addition and subtraction, X-bar theory explores the similarity between NP and VP rules.

There are only four kinds of phrase constituents:

- The head carries the central meaning of the phrase. Consider the sentence "The tall student who is wearing the red shirt asked questions of her professor, after the lecture." The central meaning is retained if we remove all non-head words: "student asked questions".

- The specifier points to the head. For nouns, specifiers include determiners ("the") and possessives ("her"). For verbs, adverbs occasionally fill this role ("quickly") .

- The complement tends to feel intimately related to the head of a phrase (e.g., "of poems" in "a book of poems").

- Adjuncts , on the other hand, tend to feel more optional (e.g., "big" in "big book").

Adjuncts vs Complement

Given that adjuncts and complements both often inhabit prepositional phrases, it is perhaps surprising that they should behave differently. The distinction between adjuncts and complements explains why this should be the case. Let us look at four behavioral differences:

Difference #1 . Adjuncts can be reordered freely.

Consider our example verb phrase:

This rule means that our two adjuncts can be shuffled, but the complement NP must retain its original position

- I will read the letter in the office before the party (Original order: valid)

- I will read the letter before the party in the office (Adj reorder: valid)

- *I will read in the office before the party the letter (Compl reorder: invalid)

Difference #2 . Indexing replacement cannot strand the complement.

For example,

- I will do so in the office before the party (Adj is stranded: valid)

- *I will do so the letter before the party (Compl is stranded: invalid)

Consider another part of speech we have not yet considered: conjunction words like "and" and "or".

Difference #3 . Conjunction words bind adjuncts together, and complements together. But adjunct-complement bindings are non-grammatical.

Consider our example noun phrase:

Three examples to illustrate how conjunction works:

- I bought the book of poems and of short stories. (Compl-compl conjunction: valid)

- The book with the red cover and the black spine. (Adj-adj conjunction: valid)

- *The book of poems and with the red cover. (Compl-adj conjunction: invalid)

What X-Bar Theory Tells Us About Memory

Earlier, I introduced the distinction between episodic and semantic memory:

- Semantic: ability to remember facts and concepts (e.g., hands have five fingers)

- Episodic: ability to remember events or episodes (e.g., dinner last Tuesday night)

Concepts are learned by extracting commonalities from episodic memories. If you see enough metallic blocks moving around on four cylinders, you'll eventually consolidate these objects into the CAR concept:

In philosophy, I suspect the concepts of necessity and contingency relate to semantic and episodic memory, respectively.

In linguistics, I suspect complements help locate concepts in semantic memory, whereas adjuncts assist episodic localization. In the sentence "I bought the book of poems with the red cover", the complement helps us activate the concept POEM-BOOK, whereas the adjunct creates sense-predictions that locate it within our episodic memory.

Takeaways

- With flat syntax trees, it is difficult to explain indexing substitution (e.g., "bought a book"→ "bought one")

- If we make syntax trees binary, by introducing intermediateX' ("X-Bar") nodes, substitution becomes more straightforward.

- Noun and verb phrases thus parameterize a more general phrase structure.

- Phrases have four kinds of constituents: head, specifier, complement, and adjuncts.

- The differences between complements and adjuncts are instructive:

- Only adjuncts can be reordered.

- Indexing replacement cannot strand the complement.

- Conjunction cannot bind across categories

- In human cognition, complements and adjuncts may correspond to semantic and episodic memory, respectively.

Source: https://kevinbinz.com/2017/10/02/x-bar-theory/

0 Response to "How to Draw Syntax Trees With Too X Bar Syntax"

Post a Comment